What is iris severe mosaic?

Iris severe mosaic (also called yellow latent disease or gray disease) is a potentially severe viral disease that can adversely affect both bulb and rhizome-forming irises, as well as crocuses. German bearded irises are particularly susceptible to the disease. Commercially produced irises and crocuses affected by iris severe mosaic cannot be sold. Thus, iris severe mosaic can have potentially significant economic consequences for iris and crocus producers.

What does iris severe mosaic look like?

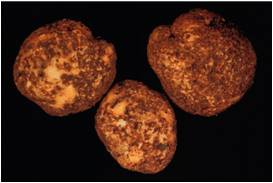

Symptoms of iris severe mosaic can occur on any plant part. Leaves, particularly middle or outermost leaves, may have pale green to yellow stripes. Younger, interior leaves often do not exhibit symptoms. Flowers may develop blotchy color (a symptom known as color break). Overall, affected plants may be stunted, producing smaller than normal flowers, and smaller bulbs, rhizomes or corms. Symptoms tend to be more severe when temperatures are cooler. At higher temperatures, symptoms are less obvious. Similarly, iris and crocus plants grown indoors tend to develop more severe symptoms than those grown outdoors. In some situations, plants with iris severe mosaic may not show any symptoms.

Where does iris severe mosaic come from?

Iris severe mosaic is caused by Iris severe mosaic virus (ISMV), a virus transmitted primarily by aphids, specifically the potato aphid (Macrosiphum euphorbiae) and the green peach or peach-potato aphid (Myzus persicae). These aphids acquire the virus from infected plants and subsequently transmit the virus to non-infected plants as they feed. ISMV can also be spread as infected plants are divided to produce additional plants.

Tools (e.g., pruning tools, knives, etc.) used when working with infected plants can become contaminated with sap containing ISMV and can serve as another means of spreading the virus to healthy plants.

How do I save plants with severe iris mosaic?

Most types of iris can tolerate low levels of ISMV. However, infected plants remain infected indefinitely and cannot be treated in any way to eliminate the virus. Therefore, you should dig up and either bury or burn affected plants as soon as you observe symptoms. This will help limit the spread of the virus.

How do I avoid problems with iris severe mosaic in the future?

When possible, plant Siberian iris (Iris sibirica) as this species is resistant to ISMV. Take care when planting German bearded iris (Iris germanica). This type of iris is very popular (and incredibly beautiful) but tends to show more severe symptoms of iris severe mosaic. When purchasing iris plants, buy only from reputable producers who have an ISMV management plan. Such a plan should include careful monitoring of stock plants for iris severe mosaic symptoms, diligent removal and destruction of infected plants, routine removal of weeds in production areas to eliminate plants that can serve as reservoirs for aphids, and applications of insecticides to control aphid populations.

When dividing iris plants, decontaminate tools routinely by treating them for a minimum of one minute with:

- 75 tablespoons Alconox® (a lab detergent) plus 2.5 tablespoons sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), also known as sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), in one gallon of water, or

- 14 dry ounces of trisodium phosphate (where allowed by state or local ordinance) in one gallon of water.

These ingredients can be ordered on the internet. If you decide to use SLS (SDS), be sure to wear gloves, safety goggles and a dust mask, and mix the solution in a well-ventilated area as SLS (SDS) is a known skin and eye irritant. Once treated, rinse items with sufficient water to remove any residues.

For more information on severe iris mosaic:

Contact the University of Wisconsin Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic (PDDC) at (608) 262-2863 or pddc@wisc.edu.

© 2021-2024 the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System doing business as University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension.

An EEO/Affirmative Action employer, University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension provides equal opportunities in employment and programming, including Title IX and ADA requirements. This document can be provided in an alternative format by calling Brian Hudelson at (608) 262-2863 (711 for Wisconsin Relay).

References to pesticide products in this publication are for your convenience and are not an endorsement or criticism of one product over similar products. You are responsible for using pesticides according to the manufacturer’s current label directions. Follow directions exactly to protect the environment and people from pesticide exposure. Failure to do so violates the law.

Thanks to Diana Alfuth, Tom German, and Kathy Shurts for reviewing this document.

A complete inventory of UW Plant Disease Facts is available at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic website: https://pddc.qa.webhosting.cals.wisc.edu.

Submit additional lawn, landscape, and gardening questions at https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/ask-a-gardening-question/.