One of the traditions of the Thanksgiving season, is to contemplate the past year and express thanks for positive aspects of our lives. Thinking of this concept in the context of plant diseases, I thought that in this month’s web article, I would discuss new diseases that I saw in the clinic in 2018 that make me thankful for having a job that is always stimulating and never dull.

One of the traditions of the Thanksgiving season, is to contemplate the past year and express thanks for positive aspects of our lives. Thinking of this concept in the context of plant diseases, I thought that in this month’s web article, I would discuss new diseases that I saw in the clinic in 2018 that make me thankful for having a job that is always stimulating and never dull.

Cranberry false blossom

The most seasonally appropriate of the new diseases that I encountered this year was cranberry false blossom. This is not a new disease of cranberry and was originally first described in the 1920’s in cranberries in Wisconsin. However, until this year, the disease has not been observed for decades in the state. Cranberry false blossom is caused by a phytoplasma (i.e., a bacterium-like organism) that is transmitted by the blunt-nosed leafhopper. Typical symptoms include odd-shaped, discolored and sterile flowers, excessive branching of vines (called brooming) and early fall reddening of foliage. Sue Lueloff [the Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic (PDDC) Assistant Diagnostician], working with Patricia McManus (the UW-Madison/Extension fruit pathologist) and Lindsay Wells-Hansen of Ocean Spray, is working to get a better sense of how widespread a problem this disease may be in commercial cranberry bogs in the state.

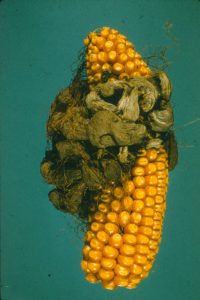

Bacterial streak of corn

This disease, caused by the bacterium Xanthomonas vasicola pv. vasculorum, was first reported in the US in Nebraska in 2016 and was found in Wisconsin this past summer. Sue Lueloff was again instrumental in confirming this disease, working with Damon Smith (the UW-Madison/Extension field crop pathologist), as well as with scientists at USDA APHIS. Typical symptoms of bacterial streak include linear, necrotic (i.e., dead) stripes (typically with a bit of a yellow halo) on affected corn leaves. The long-term impact of bacterial streak on corn production in Wisconsin is not clear. Damon and other corn researchers will be monitoring and assessing the disease in the coming years. Currently USDA APHIS scientists are attempting to complete Koch’s postulates with an isolate of the bacterium that they recovered from Wisconsin corn samples. If this is successful, publication of a first report of the disease for Wisconsin will follow in a scientific journal (something that always looks good on resume).

Verticillium wilt of Verbena

I am always watching for Verticillium wilt on new host plants, but this find caught me a bit off guard. A local greenhouse submitted Verbena leaves to my clinic in mid-summer, complaining that branches on affected plants had died back. As I microscopically examined the leaves, I noted fungal spores and conidiophores (i.e., specialized spore producing fungal threads) that were consistent with those of Verticillium (the fungus that causes Verticillium wilt). But the conidiophores were odd, looking beefier than those of Verticillium that I had seen in the past. I was able to grow a pure culture of the organism from the leaves and turned this over to Sue who once again did her molecular diagnostic magic. She identified the Verticillium as Verticillium nonalfalfae, a species I had never before encountered. I have plans to try to complete Koch’s postulates with this organism, and if successful, I will be able to publish a first report ever of Verticillium wilt on Verbena.

Zonate leaf spot

This disease, caused by the fungus Grovesinia moricola (formerly Cristulariella moricola), has been on my plant disease bucket list for years, ever since I saw drawings of the microscopic, tree-like reproductive structures of the fungus in one of my plant disease references. This summer, Brianna Wright, the Marathon County UW-Extension horticulture educator, emailed me photos of maple leaves with circular necrotic spots with concentric rings. My fungey senses (the plant pathology equivalent of Spiderman’s spidey senses) immediately went off, and I begged Brianna to send me a sample of leaves. She graciously did, and sure enough, there were the itsy-bitsy tree-like structures characteristic of Grovesinia. Interestingly, the exact same day Brianna’s maple leaves arrived, I also received a grape leaf sample for another part of Wisconsin with exactly the same pathogen and disease. Oh, the irony. It took me 20 years to see this disease for the first time and then I received two samples on the same day.

So there you have it, a sprinkling of the diseases that make me thankful to be a plant disease diagnostician. That said, as I reread this article, it dawns on me that what I am even more thankful for is having Sue Lueloff as a colleague in my clinic. Her molecular diagnostic skills have greatly enhanced the services that the Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic (PDDC) has been able to provide over the past year. Happy Thanksgiving to her and to all of you!

To learn more about common diseases and disease management, explore the PDDC website (https://pddc.qa.webhosting.cals.wisc.edu/) and in particular, check out the fact sheet section of the website. Also follow the PDDC on Facebook and Twitter @UWPDDC to receive updates on emerging diseases and their management.

June 1 marks the beginning of Hurricane season in the Atlantic and while full-blown hurricanes do not reach Wisconsin, their effects (and those of other seasonal winds) can have an influence on plant diseases.

June 1 marks the beginning of Hurricane season in the Atlantic and while full-blown hurricanes do not reach Wisconsin, their effects (and those of other seasonal winds) can have an influence on plant diseases.