What is bacterial wetwood?

Bacterial wetwood, also known as “slime flux”, is a visually frightening-looking, but typically non-lethal, disorder of many types of deciduous trees. This disorder can reduce the aesthetic appeal of landscape trees, and more seriously, can substantially reduce the value of forest trees used for lumber. Bacterial wetwood most commonly affects elm and poplar, but can also be a serious problem on aspen, maple, and mulberry.

What does bacterial wetwood look like?

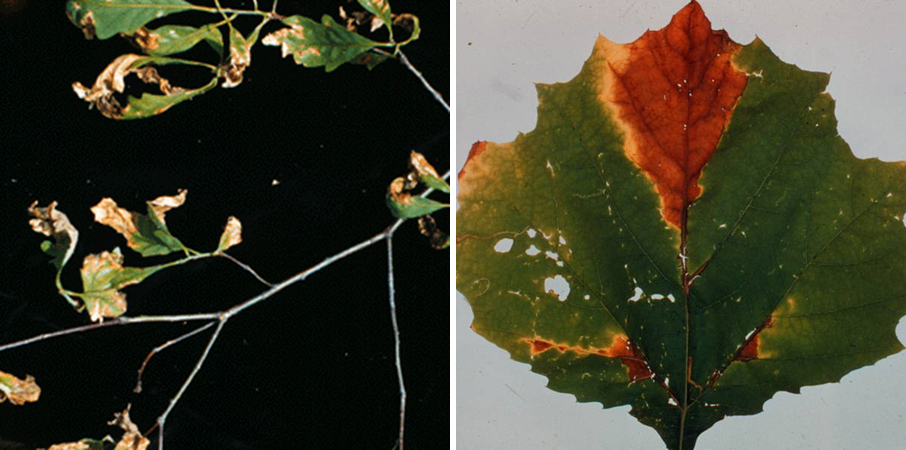

Trees suffering from bacterial wetwood have areas where liquid oozes from their trunks. This ooze may flow freely at certain times of the growing season, but then may stop flowing at others. The ooze leads to streaked, discolored, water-soaked areas on tree trunks. The ooze is often colonized by bacteria, as well as yeasts and other fungi. These organisms can give the ooze a slimy, sometimes brightly-colored (i.e., pink or orange) appearance as well as a highly disagreeable, rancid smell. Internally, bacterial wetwood can be associated with localized areas of wood decay.

Where does bacterial wetwood come from?

Bacterial wetwood arises when localized wet areas develop in the heartwood or sapwood of tree trunks. These areas are colonized by a diverse assortment of bacteria (e.g., Enterobacterium, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas and many others) that can enter trees through root, branch or trunk wounds. As these bacteria feed and grow, often under anaerobic conditions (i.e., conditions without oxygen), they can produce gases such as methane, carbon dioxide, or nitrogen gas. These gases build up pressure, causing movement of interior liquids to the exterior of the trunk where they escape through wounds and cracks.

How do I save a tree with bacterial wetwood?

Bacterial wetwood is a chronic disorder and affected trees cannot be cured. To limit the unsightly staining of bark caused by bacterial wetwood, try to identify where the ooze is exiting from the trunk and insert a long, plastic tube at this location to direct the ooze away from the trunk and to the ground at the base of the tree. There has been speculation that the build-up of gases due to bacterial wetwood might cause a tree to explode. However, there have been no reliable reports of this ever happening.

How do I avoid problems with bacterial wetwood in the future?

There is little you can do to prevent problems with bacterial wetwood. Many affected trees were likely invaded by wetwood-associated bacteria in the seedling stage. Developing a healthy tolerance for bacterial wetwood, when it occurs, is perhaps the best method for coping with this disorder.

For more information on bacterial wetwood:

Contact the University of Wisconsin Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic (PDDC) at (608) 262-2863 or pddc@wisc.edu.

*Mary Francis Heimann is a Distinguished Outreach Specialist Emerita at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

© 2009-2024 the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System doing business as University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension.

An EEO/Affirmative Action employer, University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension provides equal opportunities in employment and programming, including Title IX and ADA requirements. This document can be provided in an alternative format by calling Brian Hudelson at (608) 262-2863 (711 for Wisconsin Relay).

References to pesticide products in this publication are for your convenience and are not an endorsement or criticism of one product over similar products. You are responsible for using pesticides according to the manufacturer’s current label directions. Follow directions exactly to protect the environment and people from pesticide exposure. Failure to do so violates the law.

Thanks to Mike Maddox, Patti Nagai and Christine Regester for reviewing this document.

A complete inventory of UW Plant Disease Facts is available at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic website: https://pddc.qa.webhosting.cals.wisc.edu.

Submit additional lawn, landscape, and gardening questions at https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/ask-a-gardening-question/.