What is herbicide damage?

Herbicide damage is any adverse, undesired effect on a plant that is caused by exposure of that plant to a pesticide designed for weed control (i.e., an herbicide). Any plant can be subject to this problem.

What does herbicide damage look like?

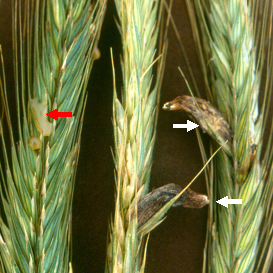

Symptoms of herbicide damage vary depending upon the plant affected and the herbicide used. Common symptoms include stems that are flattened, or that twist or corkscrew. Leaves may have abnormal shapes, sizes or textures. In addition, leaves or leaf veins may yellow or redden. In severe cases, plants may brown and die. Some plants, such as tomatoes and grapes, are particularly susceptible to herbicide damage and can be used as indicators of unwanted herbicide exposure.

How does herbicide damage occur?

Herbicide damage results when an herbicide is misapplied. Herbicides for control of broadleaf weeds are occasionally applied with fertilizers as part of a lawn care program. If these products are applied too close to ornamentals or vegetables, or are applied when there is too much wind, then the herbicide can drift (move) from the area of application into a non-treated area. Often, drifting herbicides are difficult to detect by eye because they are extremely fine mists. They can better be detected by smell. Some herbicides readily produce vapors that can begin to drift several hours after application.

How do I save a plant that has been damaged by herbicides?

There is nothing you can do after plants have been exposed. However, most plants accidentally exposed to broadleaf herbicides applied with lawn fertilizers do not receive a high enough dose to kill them. Young growth exposed to the herbicide will be distorted and discolored, but subsequent growth will be normal.

How do I avoid problems with herbicide damage in the future?

When using a lawn herbicide, follow the application directions exactly. DO NOT apply the product too close to, or in a manner that will cause exposure to, non-target ornamentals or vegetables. To avoid drift, apply the herbicide when there is as little wind as possible (< 5 mph). Apply the herbicide at low pressure to minimize production of fine mists. Finally, use amine forms rather than ester forms of herbicides as amine forms are less likely to produce vapors.

For more information on herbicide damage:

Contact the University of Wisconsin Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic (PDDC) at (608) 262-2863 or pddc@wisc.edu.

© 1999-2024 the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System doing business as University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension.

An EEO/Affirmative Action employer, University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension provides equal opportunities in employment and programming, including Title IX and ADA requirements. This document can be provided in an alternative format by calling Brian Hudelson at (608) 262-2863 (711 for Wisconsin Relay).

References to pesticide products in this publication are for your convenience and are not an endorsement or criticism of one product over similar products. You are responsible for using pesticides according to the manufacturer’s current label directions. Follow directions exactly to protect the environment and people from pesticide exposure. Failure to do so violates the law.

Thanks to Sharon Morrisey, John Stier, Ann Wied and Chris Williamson for reviewing this document.

A complete inventory of UW Plant Disease Facts is available at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic website: https://pddc.qa.webhosting.cals.wisc.edu.

Submit additional lawn, landscape, and gardening questions at https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/ask-a-gardening-question/.