What is silver leaf?

Silver leaf is a fungal disease that affects a wide range of deciduous trees. The disease has its biggest impact in fruit trees such as apple, pear and cherry, but can also affect ornamental trees such as willow, poplar, maple, oak, and elm. Silver leaf has traditionally been considered a disease of older trees that have been physically damaged or are in decline due to other diseases. However, beginning in 2017, severe cases of silver leaf have been observed on young, healthy apple trees in commercial orchards in Wisconsin.

What does silver leaf look like?

The first symptom of silver leaf is a silver sheen that appears on leaves of affected trees. The number of leaves affected can vary dramatically from tree to tree. The silver sheen develops when the epidermis of a leaf (i.e., the surface layer of cells) separates from the rest of the leaf, altering the way that the leaf reflects light. The silvery leaves may also have brown, dead patches. Leaf symptoms may appear one year, but may be less severe or even nonexistent in subsequent years.

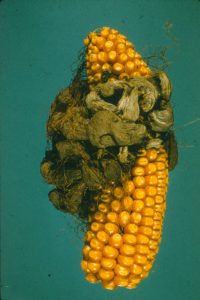

Note that other tree stresses (particularly environmental stresses) can cause leaf symptoms similar to those of silver leaf. An additional symptom that can help in identifying silver leaf is dark staining just under the bark of branches with symptomatic leaves. This staining can extend several inches down a branch. Eventually, white edged, purple-brown, shelf-like conks (reproductive structures of the fungus that causes the disease) will appear on branches and/or trunks of the diseased trees.

Where does silver leaf come from?

Silver leaf is caused by the fungus Chondrostereum purpureum. Spores of the fungus are released from conks during wet periods in the autumn and spring and infect trees at pruning scars or other open wounds (e.g., wounds from branches breaking during severe storms or due to heavy, wet spring snow). The fungus lives in the xylem (i.e., the water-conducting tissue) of infected branches, and its presence in the xylem leads to the dark staining as described above. A toxin released by the fungus moves up into the leaves causing the epidermis separation that leads to the silver sheen of the leaves. Eventually, wood in infected branches begins to decay, at which point the fungus starts producing conks.

How do I save a tree with silver leaf?

On trees with limited damage, prune out branches showing leaf symptoms. Also watch for any conks, and immediately remove branches where these are present. Removing conks limits production of spores that can lead to infections in other trees. When pruning, cut branches at least four inches below where you can see staining under the bark or where conks are visible. Decontaminate pruning tools after each cut by treating them for at least 30 seconds in 70% alcohol (e.g., rubbing alcohol, certain spray disinfectants), a commercial disinfectant or 10% bleach. If you use bleach, be sure to thoroughly rinse and oil your tools after pruning to prevent rusting.

In plantings where silver leaf symptoms are widespread, pruning out all symptomatic branches may not be practical, and the loss of that many branches might cause more harm than good. Also, trees sometimes show symptoms one year but then appear to recover in subsequent years. Therefore, instead of pruning symptomatic branches, consider marking diseased trees. Carefully watch the marked trees each year to see if symptoms reoccur or if the trees lose vigor. If trees lose vigor and/or conks become visible, then the trees should be removed. Because the silver leaf fungus limits water movement in infected branches, make sure that affected trees receive adequate water. In general trees should receive approximately one inch of water per week during the growing season from natural rain and/or irrigation. Eventually infected trees will likely decline to the point where they should be removed. In some instances, monitoring trees may not be feasible. In such situations, removing trees the first year that they show silver leaf symptoms may be the best management option.

Any branches or trunk sections removed from trees with silver leaf should be disposed of by burning (where allowed by local ordinance) or burying.

How do I avoid problems with silver leaf in the future?

Whenever possible, prune trees during the winter during dry periods when temperatures are below 32°F. If you must prune during the growing season, only prune during dry periods. Pruning at these times will decrease the risk of infection by the silver leaf fungus through pruning wounds. DO NOT use pruning paints or sealants when pruning. At this time, there are no fungicides for silver leaf control.

For more information on silver leaf:

Contact the University of Wisconsin Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic (PDDC) at (608) 262-2863 or pddc@wisc.edu.

© 2019-2024 the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System doing business as University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension.

An EEO/Affirmative Action employer, University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension provides equal opportunities in employment and programming, including Title IX and ADA requirements. This document can be provided in an alternative format by calling Brian Hudelson at (608) 262-2863 (711 for Wisconsin Relay).

References to pesticide products in this publication are for your convenience and are not an endorsement or criticism of one product over similar products. You are responsible for using pesticides according to the manufacturer’s current label directions. Follow directions exactly to protect the environment and people from pesticide exposure. Failure to do so violates the law.

Thanks to Lynn Adams, Annie Deutsch, and Bryan Jensen for reviewing this document.

A complete inventory of UW Plant Disease Facts is available at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic website: https://pddc.qa.webhosting.cals.wisc.edu.

Submit additional lawn, landscape, and gardening questions at https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/ask-a-gardening-question/.